The fatal stabbing of Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll by a Muslim neighbor prompted widespread condemnation but no ideas on combating a nebulous phenomenon.

The fatal stabbing of Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll by a Muslim neighbor prompted widespread condemnation but no ideas on combating a nebulous phenomenon.

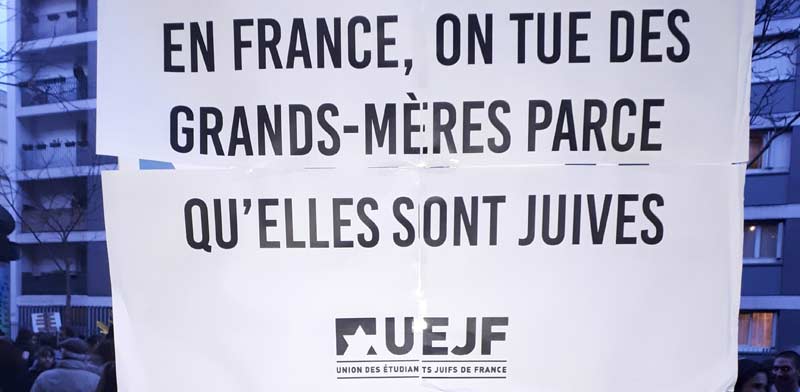

It was cold and rainy for most of the day, but by 5 pm the sun began to shine, helping to bring out a large crowd of between 10,000 and 20,000 people for a march in memory of Mireille Knoll. On March 23, the 85-year-old Holocaust survivor was stabbed to death by her longtime French Muslim neighbor, who with a homeless accomplice then set fire to her apartment. It was quickly judged to be an anti-Semitic act by police and justice officials. Most marchers were Jewish, according to those present, but a coterie of politicians, associations, Gaullic French and Muslims also turned out. Most of the press coverage focused on the presence of far right-wing National Front leader Marine Le Pen and far left “Insoumis” party head Jean-Luc Melanchon. They had been asked not to attend by Jewish groups such as the CRIF, the National Jewish Student Union, and the Sons and Daughters of Jewish Deportees. Both extremist leaders were evacuated by police after short appearances in the crowd that provoked small scuffles and chanting against their presence. The controversy over their presence was a political distraction from the main issues, a sidebar of in-fighting amongst government and opposition. The son of the deceased elderly woman said he had no problem with their presence. And the fact is, there are French Jews, Arabs and Africans who vote National Front. Other protesters noted that few Muslims had come out to march, and no Muslim associations, with one exception. Made up of black African and North African Arab religious leaders, the Conference of Imams of France, led by Imam Hassen Chalgoumi, based in the Paris suburb of Drancy, was present,

“This killing was awful and intolerable,” said Chalghoumi. “France must crack down harder on the spread of radical Islam. Many young Muslims are fed anti-Semitism in the margins of French society. There must be more surveillance in prisons, and websites that incite hatred of Jews and of western values should be shut down.” This is, of course, more easily said than done. But this is the heart of the matter.

Tunisian-born Chalghoumi is the closest of all Muslim figures in France to the Jewish community, and the most interviewed by the French press, and perhaps for both reasons is disliked by many French Muslims, but that is another story.

Several years ago, his house was ransacked and he faced death threats from Islamic radicals after taking his group of imams to Israel and Palestine, so Chalghoumi today lives with 24 hour protection by two French plain-clothed policemen.

“I think young Muslims in France are stuck between political extremes, and don’t know which way to turn,” commented marcher Katherine Levy Franchi, “so they get suckered into the radical movements. I am happy to see him and the other imams here today,” she added, motioning to Chalghoumi nearby. “As for other Muslims here, it’s hard to say. But my friend Naima is here somewhere.” Born and raised in Morocco, Naima Moghir, professor and association director, was quick to say, “nobody in his right mind could stab an elderly woman to death, as this guy did, especially after knowing her for years. How did this happen? I don’t know.”

She talked about parents and schools. “In Morocco, this could never happen because parents and the state have a clear role,” Moghir said. “But here in France, immigrant parents, often uneducated, are overwhelmed by work and children who are French born. They lose control. And the schools have not fulfilled the roles they should play. The school system is guilty of not properly guiding these kids and offering them the same opportunities as other French kids. That creates empty spaces. What they call religion has never played such an aggressive role in their identity as now, filling those spaces. But this is not religion; it is ignorance.” Like Chalghoumi, she said the words of imams must be closely followed and regulated, “as is done in Morocco,” so certain amongst them cannot spread hatred of Jews and western society. The cortege was moving. Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo passed by. “I have no statement to make,” she told me. A number of elected officials followed. There were a lot of them present, too many for some. Staring at them was Claude Pierre-Bloch, an elderly member of a distinguished French Ashkenazi family, himself the victim back in 1996 of an anti-Semitic kidnapping “to pay for Palestine”, he was told, then released unharmed. “They didn’t see this coming, all this radical Islamic violence,” he said, motioning to the politicians. “I think the French are in denial about all this. It is war, but it is sneaky and underhanded.”

“I think there are too many politicians here,” commented his 22-year-old grandson, Raphael, who works in cinema. “I’m not on any political side. The politicians don’t know what to do with all this. My generation has little faith in politics.”

So what is all this radical Islamic violence, for lack of a better name? How did it develop in France and the rest of Europe, carried out almost exclusively by young men with French and European passports? In the crowd on Boulevard Voltaire, I greeted a former head of a major Jewish organization here, now out of the game, so to speak, and back in the world of jurisprudence. According to him, 20 years ago and more, radical activity against Jews was directly linked to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. However wrong it was, there was a concrete political logic to it. “Today at the heart of jihadi and radical Islamic activity, there is anti-Semitism and anti French hatred, often by petty criminals driven by revenge and ignorance,” he continued. He mentioned the recent attack near Carcassonne in the south of France, in which five people were killed, including police officer Arnaud Beltrame, who volunteered to replace a hostage. “It is deeper, more serious and perhaps more nebulous than years ago, and we do not have the weapons to deal with this. We, in France and elsewhere, are not prepared for this.” On la rue de Charonne, I came upon a friend, Michel Zerbib, the editor-in-chief at Radio J, a heavily listened-to morning Jewish radio station. We walked up to Avenue Philippe Auguste together, as a stream of passers-by stopped to greet him. “Yes, the French are in denial about this,” he told me. “Many French politicians and ordinary people still do not see the link between radical Islam and anti-Semitism. And look at this story with Madame Knoll, la pauvre. The guy was her neighbor, locked up for a time for sexual aggression on a 12 year old girl. Not too bright and twisted. Some of these guys are downright stupid and that leads to blind violence. No political logic at all.”

We said goodbye, and I began to talk with a leader of the National Union of Jewish Students, Ines Ammar. She told me their offices at Paris 1-La Sorbonne were wrecked that morning, with files dumped and “Vive la Palestine” graffiti on the walls. “We have no idea who did this,” she said. I wanted to ask her about the existence of a Muslim Student Union, nothing to do with the office damage. “It exists, of course,” she said,”but we have no contact with them.” Why not? “I suppose because we function on different lines of thought.” I told her that this was too bad, and indicative of these times. She shrugged her shoulders and smiled. Now in the days that followed the march, the sun is gone. It is cold and raining in Paris, everyday. There is something very strange about this attack and certain others. Here is the list: Mireille Knoll, killed on March 23rd in the 11 th arrondissement, or district, of Paris. Sarah Halimi, attacked and killed in April 2017, in the 11 th district. The Charlie Hebdo magazine office attack, 12 pêople killed in January 2015, in the 11 th district. The Hypercacher market attack, four killed in January, 2015, in the 20th district, next to the 11th. The Bataclan theatre rock concert attack, at least 87 killed, November 2015, in the 11 th district. There were four restaurant attacks that same night. Three of them were in the 11th district, where at least 40 people were killed in all.

And Ilan Halimi, kidnapped and tortured to death in January 2006, taken from the 11 th district. So what is it about the 11 th arrondissement, on the east side of Paris? The answer is perhaps nebulous, like the war carried out by radical Islam. Some would say it is a coincidence. Many people of the Jewish faith say there are no coincidences.

Others might say this is yet another sidebar, albeit one that nobody has raised now. It is worth looking into. And meanwhile, the nebulous battle continues.

http://www.globes.co.il/en/article-thousands-march-in-paris-1001230095

Published by Globes [online], Israel business news – www.globes-online.com – on April 1, 2018

© Copyright of Globes Publisher Itonut (1983) Ltd. 2018