In the article entitled “Religion and Memory”, we have sketched a reflection about the relationship to the past, that could be shared by Jewish communities in Africa. An adage of the Sages of the Mishna: Why does the Torah begin with the story of Adam? To teach you that if one man says to another, ‘My ancestor is greater than yours’, let him answer: We all come from the same beginning, Adam. In this teaching, we can see that the Sages of old were already confronting the dangers of the discourse of the origins.

In the article entitled “Religion and Memory”, we have sketched a reflection about the relationship to the past, that could be shared by Jewish communities in Africa. An adage of the Sages of the Mishna: Why does the Torah begin with the story of Adam? To teach you that if one man says to another, ‘My ancestor is greater than yours’, let him answer: We all come from the same beginning, Adam. In this teaching, we can see that the Sages of old were already confronting the dangers of the discourse of the origins.

Adam and his story represent every human being in every place. Our reflection could only be from a pan-African point of view, because every African Jewish community is distinct from the other. The distinctions are very important, and cover virtually every aspect of these cultures. In this context, the pan-African point of view is the only one that allows us to take a look at both singularity and synthesis. For it is only the Pan-African thinkers who have studied the subject of diverse cultures and shared readings in the context of traditional African communities. Many reflections were made on the relationship of these communities with the concept of transmission and legitimization of history, and the need for a corrective reading of it after the colonial period. The discourse of the origins was immediately perceived as a danger by Pan-African thinkers, because it is too easy to manipulate to the detriment of those who convey it. The discourse in origins is easily usable for purposes of division and social fracture. For Panafricans, the concern was that these communities could be held hostage because of elements present in their cultures.

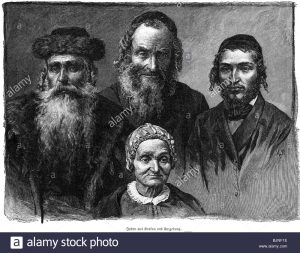

If a community’s tradition hold that they come from elsewhere in their foundational myths , this “elsewhere” could easily be turned against them, and make them foreigners in the eyes of those who would seek to dispossess them. Even millennia of historical continuity and contribution of such a community, can collapse in one look, that of racism justified by the setback of a discourse of origins. Those who were concerned with the survival of the diverse cultures of the African continent, saw themselves in the necessity to face this problematic. Their goal was to raise human dignity to millions of people, and to allow them to live together in peace. When people ask who are the Beta Israel of Ethiopia, who are the Igbo Jews of Nigeria, or the Lemba people of Zimbabwe and South Africa, among many other Jewish communities in Africa, homogeneous answers are expected. But those expecting to receive a common image, will be confronted with the reality of perspectives and trajectories different from each other. What we will find that is shared, are moral values of human dignity, transmitted in a unique way by each culture.

And it is on this point that we must not be mistaken. The pan-African vision seeks the survival and prosperity of every African culture in its own terms. We must not exclude or extinguish the voices of these cultures. Their narrations are directed towards a goal of human accomplishment, improvement, participation and surpassing oneself.

Even in sacred scriptural or oral traditions, when one speaks of ‘beginning’ it is to convey a lesson on the end, a moral teaching. The same goes for all the stories of beginnings.

To put these teachings in favor of a selective vision of superiority, is to diminish if not to obscure their primary objective, which is to enlighten us in our own lives.

The cultural distinction is important. It guarantees the survival of a whole community heritage. But this distinction is made of nuances and contextualization.

A culture can be brutalized by the use of its own elements against it.

Many cultures and traditions transmit to us stories of military glory and ancient conquest. The transmission of these epic stories is encoded in mystical or moral languages. The heroism and valor of the characters in these stories are told to inspire us to the highest values, not to explain the succession of neutral historical events.

One should not try to draw lessons about confrontations with others in these teachings.

One thing common to the Jewish communities in Africa is that they are matriarchal.

As such, explaining their perspectives is a complex task, as the perspective of matriarchal societies is different from the patriarchal world.

The notion of nation for both is different.

Patriarchal societies are often tied to the possession of the land, while matriarchal societies cultivate talents and abilities, and are often nomadic. The transmission of the stories of each community is a memory tree, in which every individual can find his place and what he needs to learn. It is not a genetic tree.

The ancestors of these stories are moral models, not mute and distant spawners.

Even the idea of priestly descent is made to honor the principles of family and community and not to create so-called superiors. The excesses of identity-based discourses barely mask the insecurity created by the experience of racism. Many people like to enhance their dignity through stories of past glories of history. Egyptologism, the reading that sees the greatness of Egyptian civilization as proof of accomplishment for Africans, is part of these drifts. This amounts to saying that modern Africa has nothing to contribute, and that nothing has happened in Africa since ancient times. But these are wounded people who convey these theories. They have before them only the Western model for which ancient Egypt is the peak of African culture. In fact this civilization is not dead, and did not remain locked in antiquity. The oasis of Siwa in Egypt was a high place of the Egyptian religion. Its inhabitants til today speak Amazigh, a living language directly related to the Egyptian language of the pharaohs. From East to West Africa, it is a language spoken by millions of Africans. The Amazigh people have had an uninterrupted history from antiquity to the present day. The context that historians call the Egyptian civilization has never disappeared, but has continued to evolve and develop in many different forms and places. Those who can only see Purity and virtue in the distant past, and which today boast over others in the name of ancient facts, suffer from lack of self esteem.

They have not absorbed the depth of traditional teachings and are using religion to boost their wounded ego. They are clay in the hands of religious cynics, and at the mercy of recuperation. We are told that Rabbi Akiba, the greatest of the masters of the Jewish tradition, was of foreign descent. Why are we taught this fact ? To make us face the potential poison of the discourse on origins.