The story never dies. More or less, it remains present in memory. A commemoration organized on the occasion of an anniversary usually brings it back to the fore. But it can also resurface through a novelist when he chooses this or that event or character as a pretext for the development of a personal fiction. The recent novel by the Portuguese writer Mario Claudio (1) is the typical example. It staged “the first massive anti-Jewish purge in Portugal” that took place in the fifteenth century. Admittedly, it is not a question of what is usually called “a historical novel” in the strict sense of the term but rather of a personal reflection on political power in general (outside of any spatio-temporal framework) to inside a story which claims to be based on facts whose existence can not be doubted. We will leave aside here the questions relating to the novelistic writing and the reception of the text (the critics published in the press at the time of the publication of the book comment exclusively on the philosophical scope of the novel) to ask us about the event which has The origin of this narration was the deportation of Jewish children at the end of the reign of D. Joao II, King of Portugal between 1481 and 1495.

The story never dies. More or less, it remains present in memory. A commemoration organized on the occasion of an anniversary usually brings it back to the fore. But it can also resurface through a novelist when he chooses this or that event or character as a pretext for the development of a personal fiction. The recent novel by the Portuguese writer Mario Claudio (1) is the typical example. It staged “the first massive anti-Jewish purge in Portugal” that took place in the fifteenth century. Admittedly, it is not a question of what is usually called “a historical novel” in the strict sense of the term but rather of a personal reflection on political power in general (outside of any spatio-temporal framework) to inside a story which claims to be based on facts whose existence can not be doubted. We will leave aside here the questions relating to the novelistic writing and the reception of the text (the critics published in the press at the time of the publication of the book comment exclusively on the philosophical scope of the novel) to ask us about the event which has The origin of this narration was the deportation of Jewish children at the end of the reign of D. Joao II, King of Portugal between 1481 and 1495.

In fact, this moment in Portuguese history has begun to arouse interest not only in the research community but also at the political level more than a decade ago. In March 1994, an article in the Israeli daily Yediy’oth A’haronoth drew the attention of its readers to a possible Jewish origin of some indigenous peoples of the Sao Tome and Principe Islands. A few months later, Moshe Liba, Israel’s ambassador to Guinea, Gabon and Cameroon, made an official visit to Sao Tome. The President of the Republic confirmed the Jewish stock of some of his fellow citizens, just like Abilio Ribas, Bishop of the island, author of a History of the Church on the Island of Saint Thomas whose first part addresses precisely the theme of the forced coming of Jewish children during this period.

Such research fills a void that can not fail to arouse suspicion and questioning among Portuguese historians today. If there is a Jewish museum in Tomar, a Society of Jewish Studies in Lisbon and a synagogue in Castelo de Vide, if more recently (1997) a chair of Jewish history was born at the University of Lisbon, the access to first-hand documents is difficult to access (2)

The sources :

Mario Claudio says he has documented the event for a long time. He cites the two main sources, namely the chronicles of Garcia de Resende and Rui de Pina. The first, valet and secretary of the King, reported the event in his Cronica D. Joao II Miscelânia (3); the second, recounted the episode in his Croniqua del Rey Dom Joham II (4). Interesting as these documents are, they give little details of the phenomenon and concern only the beginnings of Jewish emigration in these countries because, in fact, it extends over a much longer period.

Jews in Spain of Catholic Kings:

To understand the reason for this emigration (as we shall see, a real deportation), we must make a detour to Spain because its history is at that time closely linked to that of Portugal ( 5). Henry, son of John II, became king of Castile in 1454. His daughter Jeanne must normally succeed him. But the inconstancy of the Queen, the King’s second wife, incites the nobles to think that she is a bastard born of illicit loves of her mother with a favorite, Beltran de la Cueva. For this reason, she can not sit on the throne; moreover, the marriage had not been the subject of any papal dispensation. Jeanne is therefore deemed illegitimate heiress for a double title and the nobles get her sidelining for the benefit of her brother Alphonse. But he died in 1468 at the age of 15. It will be Isabelle, his sister who will inherit the Castilian crown. To establish her power, she married Ferdinand, heir to the crown of Aragon. She took the title of Queen in 1474. The event is not to the taste of all members of the nobility; a civil war ensued but the royal couple came to the end and Ferdinand became King of Aragon in 1479.

The two states are poles apart from each other. While the Aragon knows the slump with a stagnant population (1 million souls), Castile shows a dynamic economy thanks to an advantageous geographical situation: the ports of Santander and Bilbao export the wool of the sheep of the Mesta . Burgos is an important commercial center, as is Seville, where traders and travelers come from Italy and Northern Europe. Armed with this situation, the new rulers restored the royal authority over the Castilian landed aristocracy, which until then had defied it. Representatives of the crown execute decisions taken at the highest level in the cities; the Santa Hermandad, a kind of rural police force, makes order in the countryside, putting an end to multiple insurrections, notably in Barcelona.

This interior pacification would allow the rise of a policy of independence and expansion. The first act consists in the capture of Granada on January 2, 1492. An emirate, the last vestige of the Moorish presence on Spanish soil, was still present there – the other Muslim kingdoms having been conquered by the Christians – subsisted in the city by tribute. The war begun in 1481 was going to end it. The entry of Ferdinand II of Aragon was hailed as a victory of Christendom over the Muslim world and the bells rang in London, Paris and Rome. The Cross had conquered the Crescent; the defeat of the Crusaders at Constantinople in 1453 was avenged.

In terms of domestic politics, this victory would open the era of a frenzied authoritarianism. Since the capture of Granada had been carried out in the name of Christendom, it was necessary to continue in this spirit by driving out of the territory all those who did not observe the rules enacted by Rome. The high clergy encouraged this initiative and urged the king to pursue the heretics (6).

This new situation puts an end to a multi-secular organization where several religions coexisted in medieval Spain. It is known that between the 8th and 13th centuries, religious groups lived in harmony in Andalusia. The Christian Mozarabs, the Jews, the Berbers had their own religious leaders, their rites, their rules of justice. Jews in particular formed autonomous communities where religious or dietary practices were observed without constraint. Well integrated into the surrounding human environment – they had adapted the language, the costume and the Arab masters – they often serve as intermediaries at the diplomatic level between Christians and Muslims and take part in major military battles where their religious rites are crucial. since the battle of Zalaca (1086) was deferred from Saturday to Sunday so that they could take part. Suffice to say that they are not subject to any segregationist law, they circulate freely on the territory and carry no sign that would distinguish them from other communities. Some Jews even collected the tax.

However, over time, their situation would become more and more difficult. Although they enjoy a quite legal political status, the population develops phenomena of rejection that occur episodically during a fiery sermon emanating from a religious leader of another community. Number of Jews were thus massacred in 1391. Those who survived had to convert to Christianity under duress. Massacres, accompanied by massive conversions, would be repeated episodically until outright expulsion at the end of the following century. A number of them assimilated to this new religious environment; and Spinoza, a philosopher of Jewish descent but from a strain of former Portuguese (and non-Spanish) converts, noted the fact: “When a king of Spain forced the Jews to embrace the religion of the state or to To exile, a very large number became Roman Catholics and having therefore from then on all the privileges of the Spaniards of race, judged worthy of the same honors, they mingled so well with the Spaniards that, shortly afterwards, nothing of them remained, not even the memory. “(7).

But some of these “new Christians” or conversos did not deny some practices of their original religion. Judged heretical by the Roman authorities, they were hunted down by the representatives of the Church Courts under the responsibility of the Holy Office, whose creation dates back to 1231. Since 1184, in fact, the Inquisition had been established by Pope Lucius III . It provided for punishment of corporal punishment (flogging) for those guilty of high treason to religious or civil authority. More particularly, the “relaps” in other words, those who fell into heresy after publicly abjuring their original belief, were confiscated all their property; their house was shaved and they were even liable to burning. Established in Spain in 1479, the Inquisition targeted the Marranos, falsely converted Jews. It develops a general climate of denunciation. The reading of the denunciations slipped into the mailboxes of the Inquisition Court is in this respect edifying: X changes the sheets every Friday, Y refuses to consume pork, Z does not light the fire on the Sabbath and no smoke does not escape from its chimney ?? It is a hallali “(8) His action would result in a large number of collective suicides among the Jews who refused to abjure their faith, by the implementation of the autodafe, public ceremony where the convicts are exposed dressed in the garment of infamy, san benito and by a massive emigration imposed by the power. The decree authorizing expulsion, signed on March 31, 1492, resulted in the forced departure of 150,000 Jews to European countries more lenient for this population. South West France, Italy, Turkey or Amsterdam will host most of them (9). This policy is explained both by ideological and economic reasons. On the one hand, the proximity of conversos and genuine Jews maintained crypto-Judaism detrimental to the cohesion of Christian society. On the other hand, those excluded were an important manpower for developing countries that were not well known but whose economic potential gave rise to substantial benefits for the Crown.

The colonial expansion and ambivalence of Jewish society:

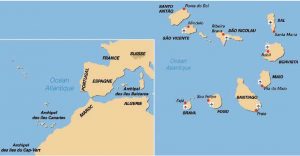

Because the country is at a turning point in its history. Having eliminated the latest manifestations of Islam, it can now ensure religious hegemony within its borders; which implies the evacuation of the Jews, who are seen as heterogeneous and dangerous elements. On one level in Christendom, the Spain of the Catholic Kings believes itself invested with a grandiose mission: to bring the faith to Jesus Christ beyond the seas on all lands inhabited by men. They are the ones who will finance the project of Christopher Columbus which aims to discover Japan and China crossing the Atlantic from the west. This initiative, which was going to profoundly change the state of knowledge in geographical terms, was part of a desire to discover the limits of our world with, in the background, the desire to benefit from its knowledge. For already at the end of the fifteenth century, the horizon has grown considerably. Under the leadership of Prince Henry the Navigator, the Portuguese had already discovered Madeira in 1418 and the Azores archipelago 14 years later. The islands of Cape Verde were reached in 1460. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias crossed the Cape of Good Hope, thereby opening the coveted Indian route. A struggle for the conquest of distant lands could not fail to emerge between Spain and Portugal. It was the treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 that brought the solution: an imaginary line is drawn linking the poles 370 leagues west of Cape Verde; the territories to the east of this marker are the property of Portugal; those who are in the west belong to Castile.

This treaty put an end to a political uncertainty. It would allow the development of the spirit of conquest on the part of these two great maritime powers at the same time as it clarified a rather confusing situation by delimiting the zones of influence of the two countries. The political consequences were most important since this agreement was going to be very favorable to Portugal: after Vasco de Gama reached India in 1498, he opened trading posts in Cochin and Deccan; the Portuguese zone of influence was soon to affect Goa (1510), Malacca (1511) and the Moluccan islands (1512), all of which territories whose spice production would be the object of a very lucrative trade.

In parallel with these discoveries, which would greatly boost the national economy, domestic policy is strengthening. The royal power is one with the high dignitaries of the Catholic Church to establish its authority and if the Cortes, an assembly bringing together the members of the high nobility and the high clergy instituted by King Alfonso II (1211-1223), put in place the court of the Inquisition in 1531, is because a climate of religious fanaticism was established throughout the country half a century ago. The first victims were the Jews. Portugal had welcomed them for a fee. Their reception was not disinterested. But quickly, an evolution is taking shape. And Spinoza is a remarkable observer when he writes after noting the successful integration of Christianized Jews into Spanish society at the time: “It was quite different from those whom the King of Portugal forced to convert, excluded from office. honorific, they continued to live apart “(op cit). In fact, the forced emigration of Jewish children to distant lands in Africa was only the first episode of a series of measures aimed at the global denial of the community as well as of the Jewish religion. While conversions to Christian rites had taken place over a century or so in Spain, it was the entire Jewish community established on Lusitanian soil that had to accept baptism in 1497. Specific Jewish practices thus passed into absolute secrecy. The ensuing crypto-Judaism was thus endowed with a force far superior to that which lives on the other side of the frontier. Especially since the Inquisition in Spain had been effective enough to eradicate Marranism in half a century; so that the persecutions against heretical Jews had become relatively rare in the mid-sixteenth century throughout the Hispanic territory. On the other hand, his counterpart, who was introduced to Portugal in 1536-1540, hunted relentlessly Jewish heretics on Camoens’ land. The Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 had no choice but to return to the land of their parents, the land of the Catholic Kings having become, through the game of political and religious strategy, a relative land of welcome. The hope of these eternal wanderers would be short-lived; the ebb of the Jewish populations in Spain could only develop the suspicions of the inquisitorial authorities of the country and the minutes of interrogations and autodafés at the end of the XVI ° century show that the victims were majority of the “new Christians” Portuguese come to seek refuge there .

The forced settlement of Jews in Africa was therefore the beginning of a policy of exclusion that was going to experience multiple episodes.

Miscegenation as a foundation for Portuguese colonies in Africa

The book of Mario Claudio is given as a starting point the sending under the constraint of the royal armies of Jewish children between 3 and 12 years to Sao- Tomé. It thus has an undeniable historical anchorage but it remains a fiction with a philosophical aim, inviting to a reflection on the religious as well as political power and more broadly on the human nature (10) – various episodes of the novel accredit the idea that the man is a predator of its own species and the hostility of the natural environment reveals a practical intelligence to ensure the survival of individuals; this leads to a stratification of social bonds operating on the basis of the economic exploitation of the weakest.

The essential characteristics of Portuguese Marranism are therefore bracketed, and the economic consequences of the repression suffered by the Lusitanian Jewish community. These are the areas we want to explore here. Without leaving the purely religious aspects of the phenomenon completely untouched, we will focus on the economic dimension, even if what was once called “the land of the Negroes”, that is to say, the coastal strip between the south of Senegal and Sierra Leone, was the object of both commercial and spiritual conquest.

This enterprise obviously had a mercantile end – the trade in spices and Sudanese gold was a source of huge profits – but it was also driven by an ideology centered on the figure of the legendary Priest John, who would have lived in East Africa. in the twelfth century and a message of 1165 would have incited the Christian rulers to make an alliance with them to develop evangelization to new continents and thwart the expansion of the Islamic movement (the legend was going to have long life since the XIV ° century, it was believed to have discovered his kingdom in present-day Abyssinia).

Begun in 1492, the exodus of Portuguese Jews (and more widely those of the Iberian Peninsula) was later relayed (XV and XVI centuries) by the Jews settled in the Netherlands. The two movements are to be distinguished: the first was engaged under duress for reasons both religious (the Portuguese Jews were considered heretical) and economic. The second was voluntary; the members of the Jewish community of the Netherlands expatriating themselves to develop a nascent trade between Africa and the most economically powerful nations of northern and southern Europe.

We will come back to these differences later. For now, let’s take a look at the events that led to the Portuguese presence in Africa. The mid-fifteenth century was crucial from the historical point of view since in 1445, Ca’da Mosto discovered some Cape Verde islands, including that of Santiago and moved to Goree and that the following year, Nuno Tristao docked in Guinea Bissau. Then came the troop to pacify the region so that trading desks could open. Plagues and raids were numerous if one believes the stories of journeys of this time. But this policy is not enough to make the region a Portuguese land. Beginning in 1460, the Crown’s strategy changed. After a war of conquest, the results of which were disappointing both commercially and religiously, it established peaceful relations with the leaders of the different kingdoms that shared the area. This strategy will have a twofold consequence: on the one hand, some African sovereigns accept the baptism and evangelization of their territories. King John II of Portugal (1481-1495), like his successor D. Manuel (1495-1521) was “lord of Guinea” and maintained close relations with the king of Congo. He received the Prince Wolof Benoim at his court in 1488. He was baptized there and took an oath of fidelity to the Crown. The second consequence of this policy is economic: by manifesting the will to collaborate with the Africans, the Portuguese royal power had in view to develop its own wealth by appropriating those of the ground and the recently discovered environment. But whether religious or commercial, relations between Portugal and these African territories were contentious and very uncertain.

Regarding the field of evangelization, everything was not self-evident. The devaluing look of the whites on the blacks makes that the first are viscerally wary of the second ones, these “lost souls, without religion, that it would have to bring back in the right way”. And even when a great African has embraced Christianity, he remains a heretic or even a traitor in power. Benoim made the sad experience: accused of conspiracy against the interests of the Portuguese kingdom, he was executed on his return to his homeland. At a more general level, the Franciscan missionaries working in the present-day Guinea Bissau faced the practices of Islam strongly anchored among the local populations. And 150 years separate the discovery of the Senegambian ensemble of the construction of the first church in Guinea, which was born around 1590. The exploitation and commercialization of local wealth were also problematic. The Portuguese had trouble with the Buramos, a population settled in the area of Cacheu who fought a fierce battle for 3 days (11) as reported by the Jesuit Manuel Alvares in 1616. However, the settlement had installed as early as 1590 or small ports of call. They served, of course, the interests of the metropolis, but in return, the whites were obliged to pay taxes and to pay back part of their property to African sovereigns.

At this point, we find the conversos. They played a crucial role in dealing with aboriginals. They were called “lance” because they “threw themselves among the blacks” or tangomaos because they served as intermediaries between the natives and the Portuguese. This socio-economic status was an extension of the situation they had experienced in Spain; it was necessary in the African soil, to show cunning, dissimulation, highlighting the interest of the African kings to bind the Whites while they defended that of the latter; as they knew so well when they pretended to have become fervent followers of Catholicism when they had not reneged on the rites of Judaism. This type of man who must be described as adventurer would continue in Africa throughout the sixteenth century as trade between the metropolis and the black continent would develop. This state of affairs is due to the very great ability of Jews to adapt to the economic context in which they must live, but also because the Holy Office was ineffective outside European borders, which allowed new Christians living in Guinea and the neighboring territories to reconnect with their original religious practices, provided that the geographical environment has lent itself to it (12).

The chronicles of time give little information on their number, but it is permissible to think that it was relatively small. In any case, they did not strain. The departure of the Jews ordered by King D.Juan II was going to change things in depth. It was no longer only a question of bringing the message of Christ to a foreign land and of building commercial links with local power; it was a question of exploiting the natural and human resources that it concealed. From then on, the policy of expansion was to take on a new dimension; the aim being to constitute a true Portuguese empire by the military, religious and economic conquest of territories exceeding national borders. But the first contacts established in Cape Verde and Sao Tome had shown the inhospitable side of these places.

The island of Santiago was subjected to an endemic drought which prohibited the presence of a true vegetation and thus a profitable agriculture. As for that of Sao Tome, so named because discovered in 1470 by Joao de Santarem and Pedro Escobar, the day when the calendar honored this saint, it was quickly known as the lizard island because of the reptiles and giant crocodiles that populated it. But by its geographical location, Sao Tome proved an essential relay to organize expeditions to India, land of all wealth.

Faced with the lack of enthusiasm of the natives to settle on these lands, the King of Portugal had no other choice but to schedule the departure under the constraint of the excluded of the kingdom that is to say the condemned prisoners to death – the sentence was then commuted in the form of a deportation – and some marranos children from the Spanish Jewish community refugee on its territory whose age was between 2 and 14 years. A Jewish witness at the time, Samuel Usque adds a precision of importance: “As my children (the members of Jewish families) had left Castile in a hurry, we had not had time to register them and nobody had checked their number. When this census was taken, it was found that the number of those who had entered exceeded six hundred families. The king decided that the surpluses would be his prisoners and his slaves. From then on, he could humiliate the Jews for his tragic designs. No redemption was possible “(13). Before their departure, the children were baptized with authority and with great pomp. According to Usque, “several women threw themselves at the feet of the King, asking for permission to accompany their children, but that did not awaken a spark of pity at home. A mother?? took his baby in his arms and without paying attention to his cries, threw himself from the boat into the disassembled sea and drowned, kissing his only son. (Mario Claudio has masterfully painted the scene). The same chronicler adds that, arriving on the island, the deportees were thrown to the ground and abandoned without mercy. Almost all of them were devoured by crocodiles and those who escaped these reptiles died of hunger and abandonment. Only a few were miraculously spared by this abominable fate. Other documents attest to the cruelty of places, but over time, the way they look at the community of Jewish children landed by coercion is changing. Yits’haq Avrabanel notes for example: “There are many children expelled from Spain ?? deported there 14 years ago ?? They have multiplied and form the majority of the inhabitants of this place

Begun in 1485 (or a year later according to other documents), the settlement of Sao Tome accelerated with these new arrivals (the other islands of the archipelago would be occupied later -Principe welcome the Portuguese in 1500 and Ano Bom in 1503). It will also be structured under the aegis of a Portuguese notable named Alvaro da Caminha, first administrator of this land and we can consider, without exaggerating the facts, that the departure of Jewish children by force in 1492 has been origin of the phenomenon of Portuguese colonization in Africa.

Mario Claudio’s novel puts forward the phenomenon of miscegenation to explain the survival of these young Jewish deportees. This is not a mere effect of the fictional work done by the novelist; many documents from this period attest to the practice of miscegenation among new Christians, whether in Sao Tome or on the Petite Côte. Living among the natives, they adapted the language and the collective morality of the natives without undue problems without denying the values that made them Portuguese Jews. The archives underline with amazement the success of this integration. Thus Alvares de Almada notes that around 1540, the kings of the Saluum (small territory around Joal) claimed to reign on the Pai dos Brancos because they had assimilated whites as their subjects and punished heavily those who stole or insulted them (14). The Jesuits who report their stay in these places also note that the Portuguese settled among the blacks adopt their way of being: “they go naked to attract benevolence and naturalize themselves with the kind of Kingdom in which they trade, mark themselves the body with an iron until the bleeding, and they make many tattoos which, after the addition of certain herbs, take the form of lizards and serpents. The assimilation could go to the highest level of the political edifice since Joao Ferreira took in marriage one of the girls of the king of Grao Fulo. Africans called him Ganagoga, literally “the man who speaks all languages”. This is important since the understanding of local languages by whites (especially Jews) allowed the establishment of commercial relations between Portuguese traders and their black counterparts.

Despite this positive side that was historically essential, the African Jew was never accepted by the ecclesiastical authorities of the time. His physical appearance as his adherence to certain values of the ambient human environment was the sign of an extraordinary monstrosity. They called him cristianos criollos and saw in him the result of an uncontrollable physical and cultural hybridity. The fruit of the unions with black-skinned girls – the criollos (Creoles) – seemed unnatural to them and they had no harsh words for “these barbarians and others of their descendants mixed with Portuguese blood”. Their way of life and their physical appearance shock the Occidental regardless of his nationality. Richard Jobson, English navigator who treads the soil of Gambia in 1620 writes: “They are Portuguese as they call themselves and some of them look like them, others are mulattoes, between white and black, but most are as black as the natives of the country. They are grouped by two or three in the same place and are all married, or rather live with black women of the country, which they have children. Nevertheless, they have neither church nor priest nor any religious order. It is clear that those who are in this state are those who have been banished or have fled from Portugal or the islands. “(15) Especially as strictly religious, some practices from Judaism persist among them . Pedro da Cunha Lobo, a Catholic bishop who had visited Sao Tome had the opportunity to see it in October 1532, when the Creoles descendants of Portuguese Jewish emigrants celebrated the Simchat Torah: for three consecutive days they celebrated the end of the reading of the Torah that concludes with the death of Moses and the discovery of the promised land. Hence the particularly noisy ritual that makes the event present (16).

Despite the general reprobation of the Catholic Church (17) and the fact that the Creoles are considered as not being part of the Portuguese population, the phenomenon of diversity has grown over time. A document dating from 1546 put the number of 200 new Christians established in Guinea, and miscegenation is also practiced in Cape Verde and Sao Tome.

A new economic situation:

The situation was going to change very quickly. Since the Portuguese authorities wanted to develop the exploitation of the natural wealth of the newly conquered countries and turn them into commercial platforms, the legislation needed to be relaxed and to allow a rapid increase of the emigrant population of Portuguese origin. Since most of them were men who exiled themselves as a result of the deportation of Jewish children, the only way to ensure a high birth rate was to allow their union with girls in the country by law. From 1515, a royal decree authorizes each Portuguese settler (povoador) to own a black slave. Miscegenation became commonplace. The African concubine, like the children to whom it gives birth, has a particular administrative identity recorded in a letter of privilege (alforria). The religious ideology that has prevailed for more than a century is therefore defeated in the face of economic urgency; the power of Lisbon having understood that the first occupants from the metropolis in Africa had no other salvation to ensure their survival than to assimilate to the host populations. The law therefore supports a pre-existing state of affairs.

Why such a change ? The first reason is the production and marketing of a new product (for the time): sugar cane.

Let’s take a look at his story. The cradle of this plant would be, it is believed, New Guinea. But very early it is found in Fiji, Indonesia and India. The Ramayana, a poem written in Sanskrit dating from the third century BC, evokes a feast with tables covered with sweets, syrup, and chewing sticks. On that date, she has already won the Middle East thanks to the Persian armies of Darius who introduced her but she remains a mere curiosity and is not yet cultivated. It is the Greeks who, in the 1st century after Christ, will extract the sugar because they buy the cane to the caravan merchants from Asia Minor. Gradually, the plant is produced in Syria and on the banks of the Nile then it is exported to Cyprus and the Balearic Islands and from there enters the south of Spain. France and Italy do not really discover it until the twelfth century when the crusaders bring it back from Palestine. Already the Turks know how to refine cane sugar and make pastries that delight the caliphs. The Venetians are also closely interested in the manufacture of this commodity; they then established their hegemony over commercial transactions in the eastern Mediterranean, which enabled them to supply this luxury commodity to the royal and princely courts from the 15th century onwards in the important of Babylon, Malaga, Damascus or Cyprus. But Portugal, which has gained a considerable advantage in terms of maritime trade, is posing as a rival of Venice. In 1418, Madeira is annexed to the Crown and as the climate and the soil are very favorable to him, the sugar cane there knows a rapid rise. Sugar is already a sign of great wealth and will remain so for at least two centuries. It was used not only as a spice but also for decorative purposes. In 1574, the future king of France Henri III was received with great pomp in Venice. The statues that adorned the banquet hall were made of sugar, as were the guests’ table settings. And the craftsmen of Murano did not work only the glass; For the big occasions, they made chandeliers in spun sugar, the height of pomp for the richest of the city of the Doges ?? Such a craze, such a demand, which is constantly increasing from a very affluent clientele, could only encourage the development of this activity. The plant was successfully introduced on the land of Sao Tome and the archipelago became in the middle of the sixteenth century the main producer of sugar. But the maintenance of the canes, the harvesting of the stems and the work in the sugar refinery require a large and robust workforce. Force was to find arms to work in plantations and factories. The deportation of Jews and Portuguese proscribed being no longer appropriate, they could come only from the African labor force. In 1493, the first Portuguese settlers settled on the island of Sao Tome. They come from Madeira and bring with them sugar cane plants. The first slaves appear on the archipelago. They are aboriginals. During the next century, they will be relayed by their brothers Benin and Congolese (Congo-Brazzaville was then called Rio Congo).

Thus, the ever-increasing needs for sugar explain in part the considerable development of the slave trade in Africa from 1550 onwards. The painful record of slavery in Africa will not be opened here. “This old demon slumbering in the history of humanity” has sparked so many studies, symposia and polemics that it would be futile to want to bring new elements. It will be noted simply that before the arrival of the Portuguese on the continent, the trade of men as a pure merchant product was practiced in the kingdom of Tekrour (French term in the form Toucouleur) in present-day Senegal and that Serer adopted the laws slavers of Djolof. In 1455, the Venetian navigator Ca’da Mosto, working for Portuguese interests, recounts that Zucholin, king of a region of Senegal, “maintains his economic power by looting several slaves on the country, as on his neighbors, of whom he uses himself in many ways, and especially to cultivate his possessions. He sells a large number of them to the Arab merchants and also delivers them to the Christians since they began to contract goods in these countries “. Recent research on the slave trade has highlighted the central role played by local rulers in enslaving millions of Africans (18). There was therefore a favorable ground for the establishment of a vast trade in human beings organized from the lands conquered by Portugal in this part of the world.

If the Moors were subjected to slavery after being captured after battles or sieges, their African brothers were enshrined as objects with exchange value. They are bought at a fixed price just like livestock or any product that enters a commercial circuit. The slave is a commodity that interests the buyer for various reasons and not just for his work force. Fourteen years before the writing of this travel report, Adahu, a Moorish nobleman imprisoned by Portuguese troops, proposed to buy his release against six of his black slaves. He was successful in 1443 (Henri the navigator thought through them get information on the country of the priest Jean, territory corresponding to Ethiopia today and supposed to hide incredible wealth). The acquisition of young men and women on newly annexed lands such as the island of Arguin (1443) but also among Moorish prisoners became commonplace at the end of the fifteenth century; in 1552, these “foreigners” represent 10% of the population of Lisbon. The capital has no less than 70 slave traders. The practice of slavery was not new when the Portuguese set foot on the African continent. Before being done by the Europeans, everything suggests that slavery practices were firmly established in the kingdoms of the Senegambian region and more broadly among those in the coastal areas located further south between Port-Seguro (Togo) and Lagos in Nigeria .

This state of affairs alone could not explain the development of slave traffic. Ca’da Mosto, to which we have already referred, gives us firsthand information on the subject: “Some slaves,” he writes, “once baptized and spoke the language of their master, were embarked aboard the caravels and sent to their congeners. They became free men after they brought back four slaves. Portuguese law thus provided for the granting of freedom to a slave who, by imprisoning four of his brothers of the same color, would hand them over as slaves to the representatives of Portuguese power in Africa. In this way, the latter found partisans ready to sell their peers and the means to provide the necessary labor for the development of newly conquered territories.

That said, what was the role of the Jews in the slave trade of Africa? The exiles of metropolitan origin who had been forced to live and work on the newly colonized lands of Africa quickly became a staple: “This mixed race society was soon to become slave traders when the people of Sao Tome were given money. king (of Portugal) the privilege of “redemption”, on the African coast in front of the archipelago “notes Francoise Latour da Veiga Pinto (20). This inclines to think, even if the statistics are sorely lacking here, that the first descendants of the Jews deported to the black continent played the role of “beaters” in the slave trade.

Things were going to evolve through the Dutch Jews as well as by the “new Christians” recently emigrated to the New World or what was then the Ottoman Empire. To grasp this situation, one must go back to 1492 and correct what has been said about the expulsion of Spanish Jews on that date. 160.000 Jews flee the Spanish land but Portugal was not the only country of reception for these excluded as our intention suggested it; 90,000 of them go to Italy, 25,000 to the Netherlands, 30,000 set their sights on France and as much in the Maghreb countries, for the most part dedicated to trade. In doing so, the banished did not enter unknown territory because, to take only the only French example; other Jewish families had preceded them on the paths of exile. This was the case in 1349 when Jews living in Dauphine and Franche-Comté were expelled and found refuge in the land of Dante and Luther; the thing is repeated in 1491 for those residing in Brittany; in 1498 for those settled in Provence; the banishment of the Jewish population was to be confirmed in 1615 by Louis XIII. When the return of the Jews from the Spanish territory pronounced by Ferdinand and Isabella on March 31, 1492, there is a consequent Jewish diaspora beyond the borders, especially in the Ottoman Empire. Some, like Joseph Nasi, occupy an important diplomatic position with the Sultan; many have become experts in transnational trading and trade with partners beyond the seas. The Sephardim of Constantinople and Salonica already formed in the 13th century an important and indispensable link between certain large merchants settled in the Eastern, Mediterranean and Nordic countries (more precisely in Amsterdam and Antwerp). When a new Sephardic emigration settles on the Senegambian coast in the ports of Joal, Portudal and Ruffisque where trading posts are already built, at the end of the 16th century – that is to say with the union of two Iberian crowns – its members are already part of a network of solidarities both family and financial. It is still difficult to reconstruct in detail the exchanges between Jews working in Africa, Italy, Greece, Spain or Belgium, but we know that the “new Christians” have played a leading role. This is due to the Portuguese conquests in the 15th century and the Turkish expansion towards the Balkans, which profoundly and durably altered the general pattern of traditional trade. Sea routes have diversified; the distances covered by boat, made possible by the progress of navigation techniques, have become much larger. This new configuration of maritime commerce required accounting and credit knowledge that was not available to most Genoese, Venetian or Florentine merchants (21). In addition, family or business ties (often both) were already well established and allowed for transactions between Jewish traders in Seville, Antwerp, Venice, Salonica, Madeira and Spain. Amsterdam and a few years later from Brazil. Those who emigrate to Africa know from the outset that they will be able to trade with their religious brothers who have remained in Europe.

This is the case of Diego Fernandes and Felipe de Nis who leave respectively Madeira and Cape Verde to settle in Brazil and develop the sugar cane trade there. At the beginning of the 17th century, those who decided to leave their native land were going to swell the small Jewish population that took root in Guinea and Cape Verde.

Jews in Africa: A religious heresy, a commercial necessity:

Seen in this light, the Jewish community emerging from the new migratory wave in Africa at the beginning of the 17th century seems to be a valuable ally for the Portuguese Crown since it allows it to make substantial profits from the emerging economic situation. with maritime expansion. In fact, the situation is much more ambiguous for a double reason. The first is religious. .

We know that at that time, political affairs and the economic stakes it generates are closely linked to religious ideology, which focuses on the evangelization of the conquered peoples and the spread of Christianity. But if the tangomaos born of the union of the first Jews who arrived on the continent with black women are assimilated to the local population and are perceived as Africans in their own right, it is not the same for the new emigrants, ” men of the Hebrew nation, who after being baptized, passed to the law of Moses and proclaimed themselves as Jews. ” Documents collected at the National Archives of Torre do Tombo in Lisbon provide precise information on the religious behavior of these newcomers; they emanate from Portuguese officials stationed at Cacheu or from Jesuit fathers dispatched to the Little Coast by the King of Spain Philip III between 1605 and 1616, that is to say during the period of Union of the two Iberian Crowns (1580- 1640). Their conclusions overlap. On the one hand, they practice and follow their rites and ceremonies like those of Judea. While in France, their religious rituals were officially prohibited, in Africa they are observed in the open in appropriate places built by these new Jews emigrants. Several documents attest to the existence of a synagogue in Joal, otherwise it is the home of one of them who is chosen as a place of worship and meeting. These people pray together “aloud on Friday afternoons. Saturday was a holiday as if it were a Sunday. How to explain such a freedom? Francisco de Lemos Coelho remarks that “they settled here because the local kings protected them and because they could not be punished because of their religious practice”. Another archive reveals that the Portuguese living in Portudal “wanted to kill and expel them but the (African) King said ?? that his country was open and that all kinds of people could live there, and that he would cut off all those who would interfere ?? “. It is to be supposed that the tolerance of local kings served their economic interests; Jews paying a high royalty for permission to trade on their territory. These newly implanted Jews “openly judaize” (22) and some claim to be spiritual guides who give up their civil status name to endorse another one, with a much more Israelite consonance, even trying to convert “other Catholics. with money “, learning the art of practicing circumcision with instruments they brought in their luggage. It is understandable that such a Judaising zeal has worried the clergy (metropolitan or on mission in the field) as the royal power; it was a hindrance to the deliverance of the Christian message on the African continent whose populations risked eventually embrace the heresy that was Judaism, reducing to nothing the efforts of the Franciscan missionaries then Jesuits.

To curb this movement, King Philip III, in 1601, imposes on every new Christian who wishes to go to work overseas the payment of a heavy annual tax (200,000 cruzados) to the Iberian Crown. But that does not put an end to the migratory phenomenon. Portuguese Jews leave their province for Flanders (the Lusitanian colony was already important in the 13th century in Bruges) or Amsterdam. There they plunge back into the atmosphere of their religion of origin because they are welcomed in very practicing families who finance their trip towards the African coasts; or they emigrate directly in this direction and then go to the flat country, take root in the religious traditions of their ancestors and return to Africa with manufactured products or foodstuffs that they exchange for wax, oil and ivory, animal skins. They bring back very often to Guinea or the surrounding lands, members of their family, followers of the Jewish religion and who are destined to trade. If the danger they represent on the religious level is obvious, the one they arouse financially is no less so. For the transactions engaged by these men largely escape the Portuguese; these deal mainly with Dutch merchants – who have also protected their interests by building a fort on the island of Bezeguiche, another name for the island of Goree – or Iberian Jewish religion settled on land conquered by the Turks. They thus export materials or products valued by the nobility or the wealthiest notables in Europe (23). Moreover, some of them, belonging to very wealthy families, have substantial capital; they become lenders and lend money to the Portuguese so that they too can transport the goods they bought or sold to small distances.

All these data are recorded in reports emanating from clergymen or high personalities representing the royal power of the metropolis. All proposed intensive emigration and Christianization to stem Jewish religious and economic influence.

They were not listened to. But their warnings nevertheless led to a plan to expel Jews living on African lands under the Portuguese administration between the years 1612 and 1615. Black rulers, in particular that of Lambaïa on which Portudal depended, fiercely opposed when they left, not only because they received from them dadivas (donations) and taxes allowing them to trade on their territory but because these foreigners gave them weapons whose sale was prohibited to them as they were “Gentiles” (that is, pagans). In the end, the Jews were not prosecuted for heresy and the territories where they were settled did not receive massively other emigrants from Iberia.

Why did the status quo hold? Because this community served not only the interests of African rulers but also those of the Portuguese (even if, on the other hand, Jews and Portuguese from Africa were in open conflict of interests). Not only did they have enough capital to lend money at a high rate of pay to the Lusitanian traders – which allowed them to improve their way of transporting goods by cabotage – but they had carved out a place for themselves. prominent in the slave trade. Between 1609 and 1615, they supplied more than 30 ships officially exporting slaves on behalf of the Crown, not to mention those coming illegally from Seville or the Canary Islands, for a total annual of 10,000 to 15,000 individuals.

From Africa to South America:

The slavery trade in Africa which had ensured the prosperity of many Jewish emigrants was to decline from 1660 or 2 decades after the restoration of Portuguese sovereignty represented by the House of Braganza. Some of them, like Jacob Peregrino (Jacob the Pilgrim), although originally from Alentejo (his real name was Joao Freire), will end their days in Amsterdam. Others will embark for the New World. And there, they will integrate easily into the commercial and religious networks that the “new Christians” established in the Spanish colonies from 1580, when the Union of the two kingdoms favored the departure of the emigrants. Their starting point was first Brazil. From there they pushed north and reached Mexico and, moving east and south, reached Peru and the silver mines of Potosi in what is now Bolivia. A report dated 1602 addressed to the King indicates that “many Portuguese have entered the Rio de la Plata; they are unsafe people in the matter of our Holy Catholic Faith ?? In some ports they brought in our enemies and they trade with them. ” Ten years later, Francisco de Tejo, commissioner at the Inquisition court created in Lima in 1599, wanted to be even more explicit: “We take for certain that must come many fugitives, Jews from Spain and Brazil? ? ; the ease with which the Jews enter and leave this port must be remedied; but we can not help it because they are all Portuguese, they help each other and hide each other “. It is estimated that in 1643, 25% of the population of Buenos Aires was of Portuguese origin. In Potosi there were 6000 Spaniards in a total population of 13,000. The mining towns of Pachuca and Zacatecas or the cities of Vera Cruz, Mexico City and Guadalajara also sheltered a large number of Portuguese marranos in the middle of the 17th century. For the most part, they are traders whose level of wealth is variable; some are mere merchants presenting their goods on the market stall, others peddlers, others important brewers like Simon Vaez Sevilla considered the richest man in New Spain. Some evolve in other spheres (medicine or accounting). But the majority of them can read and write according to the records of interrogations provided by the Inquisitors who record their testimony and 20% of these Marranos have attended the university or a monastery to acquire a higher education.

Among these “new Christians” traders who have become powerful businessmen practice a large scale trade both transatlantic and transpacific: Simon Vaez imports in New Spain luxury fabrics, metal tools, paper, wax, oil from the country of Don Quixote but also African slaves as well as oriental products (spices, precious fabrics) that they export to Europe, just like the cochineal (aphid living in Mexico from which a dye is taken, carmine), indigo and especially silver. This vast commercial circuit that spans three continents works without fail because they occupy members of the same family. The goods which it makes enter New Spain leave the port of Seville where are chartered by his brothers and his cousins. These deal with the brothers Alonso and Gaspar Passarino, themselves partners with other traders of Jewish origin such as Duarte Fernandez and Jorge de Paz. These “new Christians” therefore concentrate enormous capital so that Olivares, favorite of Philip IV and master of the Kingdom of Spain between 1621 and 1643 has recourse to them to finance his expansionist policy.

We find here the ambiguity of the status of Jewish traders, hated by religious power but unavoidable commercially and financially for the royal power.

What was this immense fortune made of? It consisted of the commercialization of slaves of African origin and the illegal sale of certain natural wealth of the New World countries.

The slave trade is fundamental in building the wealth of the richest members of the Marrano community. This is mainly explained by the fact that between 1580 and 1640, the Iberian Crown had reserved the exclusive transportation of slaves to the New World to Portuguese businessmen who, for the majority, were of Jewish descent. In addition, the farmers charged with raising the tax to the King of Spain in exchange for a sum established by contract, made an alliance with the men in charge of the collection of slaves, who were mostly Portuguese of Jewish confession. Another piece of data that greatly favors their earnings has been smuggling. Traffickers authorized to load slaves on ships boarded more than the authorized number and in the process many goods were unlawfully introduced on the new continent. Everything was routed to Vera Cruz and Cartagena to be redistributed in the Caribbean, Mexico and Peru (for the last destination).

In addition to the slave trade, the money extracted from the Potosi mines is the source of considerable profits. He is brought by road to Buenos Aires and from there he takes the road to Europe and Brazil (24). Huge quantities are diverted from licensed channels and sold illegally by traders of Jewish descent. Among them is Francisco de Victoria, the first bishop of Tucuman, a town in northwestern Argentina today that was both a member of the high clergy and a big trader (and a big trader) and one of his brothers, Diego Perez de Acosta, who, having been a merchant in Potosi then in Peru, was burned in effigy during the burning of Lima (1605, and, helped by his brother Francisco, exiled to Seville then to Venice to end its life in Safed in Palestine Other data show the involvement of Jews in the exploitation of the human and natural wealth of the newly conquered lands, the island of Curaçao in Venezuela was an important relay for the cargoes of slaves, and most of the business was carried out by merchants from Amsterdam, whose partners in the ports of Coro or Maracaibo were responsible for delivery throughout the Americas and in the United States. s main capitals of the metropolis.

To conclude:

As we can see, the distribution channels that connect the three continents (Europe, Africa, America) work perfectly; dealing with any commodity, they were formed by the “new Christians” from the Portuguese capital for the most part and who in the long term have gained a foothold in Amsterdam, Antwerp, Livorno, Constantinople, Mexico, Vera Cruz or in the Caribbean. This population is very mobile; while some of them leave Spain, Portugal or the new colonies to escape the rigors of the Inquisition, others come to settle there to manage their affairs. They sign the accounting documents of their Portuguese or Spanish name but keep a Hebrew name within the Jewish community they claim (Joao Freire, whom we talked about earlier, called himself Jacob Peregrino as soon as he crossed the ground of La Petite Coast).

Even if their religious rites present some differences, they profess an unwavering attachment to the law of Moses. Some research on the history of Marranos and “new Christians” tends to relativize the observance of daily practices related to the Jewish religion (calendar constraints, food etc.) to favor a collective memory expressed in the precept zakhor (remember). They develop the thesis that what binds the Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal and their distant descendants scattered in the old and the new world is the omnipresence and the strength of the memory of the ancestors, persecutions, hatreds, humiliations of which they were the object at the same time as the feeling of a specificity, a “pride of the blood” (Nathan Wachtel.). It is this “community of destiny”, this “faith of remembrance” (ibid) which forms the ideological cement between the members of the commercial networks that we have mentioned. The strength of memory can not be denied; However, it must not relegate to the background the realities that punctuate everyday life, such as Jewish holidays (set according to a calendar different from that observed by Christians) and food prohibitions linked, from near or far, to an event. happy or catastrophic occurred in the Jewish people centuries ago. How many followers of the Jewish religion have perished or been forced into exile because of these practices ?

As banal as they have been, these traditions form the living memory of this community; they are embodied in terms of manners and table products by a great diversity, which proves a remarkable adaptation to the natural and human environment.

For reasons of space, we will not begin the study of the festive symbolic (dress and culinary) Jewish and the multiple manifestations by which it has materialized according to the environment and time. However, it can be posited as a working hypothesis that it was the mediation in space and duration that allowed scattered individuals to identify themselves as members of one and the same community and that respect for the past, for general as it was, could not have been sufficient to constitute the common identity of a population so scattered and mobile geographically.

The importance of Marranism in Africa is therefore twofold: on the one hand, it contributes to the emergence of an economic modernity by developing new forms of trade over much longer distances than before, on the other hand it contributes to the building of a common consciousness and now the memory of the lived experience and the salient facts that have punctuated the past of the Jews. It thus constitutes a point of articulation between economic, colonial and religious history, showing the extreme complexity of the relationship between commercial, banking and political activity and the appearance of a “religiosity”, a way for Judaisans to think of themselves. different from the Christians and to recover the religious precepts of their ancestors.

Notices :

(1) Mario Claudio: Orion – Lisboa – Publicaçoes Dom Quixote – 2003.

(2) “Who wants to work today in Portugal on the Portuguese Jews and the former Portuguese colonies can only carry out his research with great difficulty: the libraries, in a catastrophic state are unable to obtain the foreign scientific literature, which makes any serious research impossible. (Machael Studemund Halevy: The Jews in Portugal today).

(3) Text reprinted in 1974 (Imprensa National – Casa da Moeda). Garcia de Resende, a poet, musician and military architect, also left a Cancionero General, which brings together poems composed in the classes of D. Afonso V, D. Joao II and D. Manuel.

(4) Text reissued by Atlantica Livraria in Coimbra in 1950.

(5) We refer here to the book of Joseph Pérez: Isabella and Ferdinand, Kings Catholics of Spain-Paris-Fayard 1988.

(6) See Bartolomé Bennassar: The Spanish Inquisition XV-XIX Cent Paris-Hachette – 2001.

(7) Spinoza: Tractatus theologico-politicus – Gallimard – Coll Folio-Essays, p 78.

(8) Michel Del Castillo: Dictionary of love of Spain ?? Paris – Plon 2005 p 305.

(9) It should be mentioned that exile for religious reasons does not only affect Jews. Christians called mozarabes living in Islamized lands after the Moorish conquests of the seventh century, were forced to leave the places where they had been installed for generations during the reconquest launched in the tenth and eleventh centuries by the Christian kingdoms of the north (Castile, Aragon, Leon) because at the end of a setback of Muslim troops, they were considered traitors acquired by the Islamic cause. They could do nothing but flee into the Christian zone.

(10) In an interview published in the supplement das Artes e das Letras of the newspaper Primeiro de Janeiro (March 17, 2003), the author states: “it is not a properly historical novel ?? The historical episode functions as a metaphor for dealing with the issue of power and the ethnic minority that suffers from power. It does not matter whether this situation has occurred in one century or another.

(11) Nuno da Silva Gonçalves: The Jesuits and the Missao of Cabo verde (1604-1642). Lisboa – Brotéria 1996 p 58.

(12) Only some (few) Jews returning from Africa were brought to trial by the Lisbon Inquisition Court. Let us quote, however, the judgments of Antonio Fernandes and Mestre Diego in 1563. We follow here the very thorough work of Antonio de Almeida Mendes: The role of the Inquisition in Guinea – Vicissitudes of the Jewish presences on the Small Coast (XV-XVII Centuries) in Revista Lusofona de ciença das religioes. Year III 2004 n ° 5/6 p 137 – 155.

(13) Samuel Usque: Consolaçam as Tribulaçoens of Israel -Coimbra 1907. Work translated into English under the title: Consolation for the tribulations of Israel-Philadelphia 1965.

(14) André Alvares de Almada: Tratado breve dos Rios of Guiné do Cabo Verde. Text published in 1594.

(15) Richard Jobson: The golden trade or a discovery of the river Gambia and the golden trade of the Aethiopians (1623)

(16) Manuel Rosario Pinto, a priest from the island of Sao Tome confirms the existence of this ceremony among the Jewish Creoles in 1730. Rabbi Issac Louria, eminent Kabbalist of the seventeenth century, codified the ceremony: the male faithful dance around those who carry the sacred texts and women, placed on a platform overlooking the dancers, throw on these last quantity of sweets, gift materializing the words of the divine message. A candle is then lit in the tabernacle where the scrolls of the Torah will be placed because “the commandment is torch and the Torah light”. These will be stored when the candle is completely consumed.

(17) Such a point of view is fundamentally at odds with the figure of Saint Paul, who was both a Jew of origin, a Greek of formation, and a Latin in the last years of his life. Stanislas Breton (Saint Paul-PUF-1988) has shown that such miscegenation leads to a new notion of his time: the person and the concept of identity. See the profound commentary given by Michel Serres in Rameaux (Edit Le Pommier- 2004- pp 69 v).

(18) See the highly committed book of Beninese Felix Iroko: The Slave Coast and the Atlantic Treaty. The facts and the judgment of history. New Press Publications. Cotonou 2003- 207 pages. A short presentation of the book by Roger Gbégnonvi was published on the website of the journal Africultures on 03.12.2003.

(19) Felix Iroko writes “the local rulers, to procure captives, had an infinite number of them killed, the oldest were always slaughtered” p 113; The salesmen who had nurses in their contingents, tore out the babies they threw at night to the wild animals before proposing them to the captains themselves “(p.

(20) F.Latour da Veiga Pinto: »Portugal’s participation in the slave trade» in The slave trade from the 15th to the 19th century. General history of Africa. Studies and documents 2. Unesco-1979 pp. 130-160.

(21) The dynamics of trade had already led to many upheavals and bankruptcies among Genoese merchants in the thirteenth century as shown by Jean Favier in his book De l’or and spices – Fayard – 1987

(22) The expression is Sebastiao Fernandes Caçao, Attorney General of the King who at the beginning of the 17th century wrote a detailed report on the activities of the new Jews on the Wolof Coast and kept in the Ajuda Library in Lisbon.

(23) High-ranking Portuguese officials sometimes get in touch with Jewish merchants. This was the case of Joao Soeiro who had Cacheu unloaded boats chartered by his own brother based in Amsterdam, thus participating in the eviction of the Portuguese in international transactions.

(24) See Fernand Braudel: From Potosi to Buenos Aires: a clandestine road of money. Late 16th century, early 17th century in Cahiers des Annales 1949 p 154 - 158. /// Art.No .: 4391