By: Prof. Daniel Sperber.

By: Prof. Daniel Sperber.

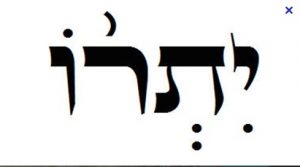

The first mishnah in Tractate Rosh ha-Shanah tells us that one of the four dates for the New Year is the New Year for trees: “On the first of shvat is the New Year for trees, according to the House of Shammai. The House of Hillel say on the fifteenth of that month.” The gemara (loc. sit. 14a) presents the view of the House of Shammai and explains: “Why? Rabbi Eleazar said, citing Rabbi Hoshaiah: since most of that year’s rain is past, and still most of the season is ahead.” Rav Hai Gaon, the last of the Babylonian geonim (11th century) was requested to interpret this gemara, and so he did. [1] But after doing so, he continued and said that the rabbis of the land of Israel – “the rabbis over there” – give another reason, namely that thus far the trees have been living off the water of the past year, and henceforth they live off the water of the coming year (according to the Jerusalem Talmud, Rosh ha-Shanah 1.2). Rav Hai Gaon added:

This seems reasonable. For this season is called in the language of Ishmael al’jamra al- taniya (= the second ember), and at this time the sap begins to flow and the trees begin to drink and come alive, and it is said gari al-ma fi al- ud (the water has entered the tree).

What did Rav Hai Gaon mean by saying that this time of year is called “the second ember”? This remark can be understood in the light of an ancient Arab legend, according to which people spend the rainy season closed up in their tents, wrapped in layers of clothing, dozing by the glowing fireplace. The flocks and herds are also gathered into their enclosures surrounding the tent, shivering with cold and waiting for sunny days and expansive pasture in the fields and hills. Then Allah is stirred by his great mercy to bring down for them three embers from heaven: one ember, jamrat al- hawi (the ember of air) comes down on the seventh of Shvat and warms the air, bringing tidings of the arrival of spring. Then the farmer wakes from his slumber, opens the enclosure and begins to send his livestock out to the fields. However they will not yet find good pasture, and the weather is still bitter cold. Then the farmer waits expectantly another seven days, until the fourteenth of Shvat, on which day Allah brings down another ember from heaven (jamrat al-mayi – the ember of water), and then the water warms up, enters the trees and makes them blossom and bear fruit once more. This makes the farmer joyful, and he sends his livestock off to the hills to pasture. However the weather is still too cold and windy to go out and till one’s fields. The farmer counts another seven days, and then Allah brings down the third ember from heaven (jamrat al- ard – the ember of the earth). The soil gets warmer and begins to be covered by tender blades of grass. Then the farmer shakes off the laziness cast over him by the rainy season, and goes out to work in the field and in his garden until evening.

Another variant of this legend about embers appears in the work of the 13th-century Arab geographer, Al-Kazwini, in his cosmography. [2] During the month of Shvat the farmers of the land of Israel gradually make the fire which warms them smaller. On the seventh of Shvat they remove one ember from the fire, because the air is beginning to get warmer. On the fourteenth of Shvat they take out a second ember, because the water is getting warmer, and on the twenty-first of Shvat, a third ember, because the ground is also warming up. The day after the second ember is removed, on the fifteenth of Shvat, they plant roses, Jasmine and narcissus. [3]

So we see that Rav Hai Gaon meant to explain the view of the School of Hillel, that the New Year for trees falls on the fifteenth of Shvat, and brought as evidence what he had heard from Arab farmers, that the trees begin to drink the warming water of the coming year. This legend draws a comparison between the farmer, sleepy in winter and awakening in the month of Shvat, and the trees, dormant in winter and awakening on their New Year. Indeed, the Torah compares trees to human beings, saying, “Are trees of the field human” (Deut. 20:19). [4]

The Sages felt kindly towards trees and cared for their welfare and health. They even said that if a tree is unhealthy, restrictions against its fruit do not apply (Tosefta, Shevi’it 1.10): “The tree may be pruned with a knife … and neither the laws of the seventh year nor concerning the customs of the Amorites are to constitute any hindrance.” In other words, one may paint a red mark on the unhealthy tree in order to announce that its fruit is allowed, and one may even do so during the sabbatical year and even if the gentiles do the same, or even if passersby might pray over it.

Just like human beings, trees have their own birthday and New Year, a sort of Bar Mitzvah, marking their no longer being orlah (their fruit forbidden because of the trees’ young age). Trees are dormant in winter and awaken to drink the water that grows warmer from the second ember in the middle of the month of Shvat, so that they can produce their fruit in due season and enable us to recite a benediction over trees and the fruit they bear.

***

Another noteworthy theme connected with Tu b’Shvat is that the fifteenth of Shvat was traditionally a day off for teachers and pupils in the Beit Midrash. On that day the Beit Midrash did not function, and the youngsters did not come to their rabbi’s house to study. Upon leaving the morning prayer service, the melamed (instructor) had to give his pupils wine and honey cake at his own expense, not theirs. [5] This date was also considered the end of the term: [6]

When the New Year for trees came on the fifteenth of Shvat, … the melamed would depart, regardless of his employer’s wishes, for he would have in mind to find another location and a city where he would be more highly respected than in his previous position, and where the pay would be better. Until the beginning of the next term the number of students would dwindle, until a new melamed arrived… And thus it would continue, until the youngsters would grow up and chirp like birds and the rabbis would not know what they are saying … and they would begin to behave superciliously … and impudence, levity and the like would increase.

During term-time, however, they were very strict in disciplining their instructors, as we learn from the records of the communities of Altona, Hamburg and Wandsbek, 1724:

It has become known to the community that there are some melameds who have been doing the Lord’s work fraudulently, letting off the youngsters from their studies on days that are not vacations, as on the past Sunday, the day after the fifteenth (of Shvat, which that year fell on the Sabbath), not only canceling studies on the holy Sabbath but also on Sunday, thereby contravening the law of the Torah and not only causing irrevocable damage but also coming under the general rule, “Cursed is he who does the Lord’s work fraudulently.” Seeing this, the community cannot stand silently by and therefore warns that such a thing shall not be repeated in the future, but that the melameds shall teach the schoolchildren regularly, and if anyone violates this rule he shall be given a punishment beyond bearing.

[1] See B. M. Levine, Otzar ha-Geonim le-Rosh ha-Shanah, Jerusalem 1933, p. 23.

[2] Vol. 1, p.76.

[3] Cf. Yom- Tov Levinsky, Sefer ha-Moadim, Part 2, Yemei Mo’ed ve- Zikaron, p. 321.

[4] In the film Lord of the Rings we see the wondrous and beloved characters known as Ents, large old and wise trees, full of kind-hearted wisdom, who play a central role in saving the world of humankind.

[5] According to Minhagei Wormeise by Rabbi Yospe Shemesh, 1673. Perhaps the widespread practice of handing out report cards on Tu b’Shvat, even though there is no vacation then, originated from this custom.

[6] Records of Talmud Torah, Kiev, 1765, appearing in: S. Assaf, Mekorot le- Toledot ha-Hinnukh be- Yisrael, Part 4, Tel Aviv 1948, p. 193.