Ancient Chinese Community Celebrates Its Jewish Roots, and Passover

Ancient Chinese Community Celebrates Its Jewish Roots, and Passover

Over the remains of the Chinese-style Passover banquet – soups with bamboo and huge chunks of fresh tofu, steamed fish and platters of crisp greens in mustard sauce – Li Penglin, 16, lifted a glass of Israeli wine from his place at the head table. Quietly but without faltering, he read out a Chinese translation of a Hebrew prayer.

About 50 guests, including several local government officials, responded with a chorus of amens, downing their thimblefuls of wine while self-consciously leaning to the left. Some poked neighbors who, unfamiliar with the Jewish custom, had neglected to incline.

It was an atypical scene on an atypical occasion: a Chinese celebration of Passover, the Jewish holiday commemorating the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt more than 3,000 years ago.

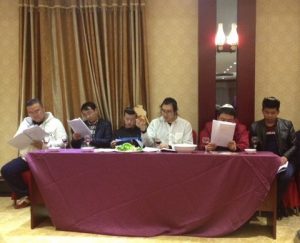

In a hotel dining room festooned with purple garlands for a coming wedding, Chinese of Jewish descent in the central city of Kaifeng came together on Friday night for a Seder, the traditional Passover meal over which the Exodus story is recounted. Just two days before Qingming, the “tomb-sweeping” festival when Chinese traditionally pay their respects at family graves, they had gathered to recall ancestors even more ancient and a world away. Eight clans in Kaifeng claim to be able to trace their lineage back to a small number of Sephardic Jews who made this fertile region their home in the 12th century, when Kaifeng was the capital of the Northern Sung Dynasty and a bustling hub on the Silk Road. But intermarriage, assimilation and isolation eroded their numbers over time. Floods and fires repeatedly destroyed the city’s synagogue, which was not rebuilt after a flood in the 1850s. The Cultural Revolution in the 1960s further quashed any lingering expressions of religious practice. These days, Jewish visitors and organizations from the United States and Israel come to the city seeking traces of the ancient Jewish settlers, financing a small Jewish community center and paying for the immigration to Israel of 15 people from Kaifeng. The Chinese government’s acceptance comes as Israel and China are actively seeking closer business ties, including in Kaifeng. Mr. Li, one of the leaders of Friday’s Seder, said he was using this reawakening tradition to better understand the past and the wider modern world. He said Torah study had been a way for him to learn about the world beyond Kaifeng and the strict Chinese education system. “When I’m at school studying what the teachers require, it’s like I’m stuck in a big house,” he said. “But I can use all this as a small window to see what life is like on the outside.”

For him, the story of Passover resonates in a particularly Chinese context. “I can use what I know about the conditions in China during the Anti-Japanese War,” he said, referring to the conflict from 1937 to 1945, “and imagine those of the Jewish people as they fled the Egyptian pharaoh’s control.”

Kaifeng Jews are proud of their Semitic roots, with some studying Torah and placing the traditional mezuza by their doorway. “I want my daughter to grow up with Jewish culture,” said Li Wei, 40, a cousin of Li Penglin’s and an investor in local construction projects who likes to go by his Hebrew name, David. “We’re Jews, after all, so why wouldn’t I?”

His 5-year-old daughter was one of four children called to sing “Ma Nishtana,” a song that asks why Passover is a night different from all others.

The prayer text for the Seder, or Haggadah, was developed by Barnaby Yeh, a Taiwanese-American convert to Judaism working for the Sino-Judaic Institute, a California-based organization devoted to the study of Jewish communities in China. In late 2012, Mr. Yeh, who now lives in Kaifeng, received scans of Kaifeng religious manuscripts from the 17th century, and has worked since then to translate the Hebrew into Chinese to create a new Haggadah for the local Jewish descendants. “I felt it important for the community to have a prayer rite they could call their own,” he said. Each table at the gathering Friday night was equipped with a Seder plate with Chinese characteristics – red jujube paste served as the sweet charoset, and a local bitter salad green as the maror, symbolizing bondage. Though there was plenty of matzo brought in from Israel by way of Beijing, Guo Yan, 35, whose Hebrew name is Esther, recalled the more meager offerings of years past.

The prayer text for the Seder, or Haggadah, was developed by Barnaby Yeh, a Taiwanese-American convert to Judaism working for the Sino-Judaic Institute, a California-based organization devoted to the study of Jewish communities in China. In late 2012, Mr. Yeh, who now lives in Kaifeng, received scans of Kaifeng religious manuscripts from the 17th century, and has worked since then to translate the Hebrew into Chinese to create a new Haggadah for the local Jewish descendants. “I felt it important for the community to have a prayer rite they could call their own,” he said. Each table at the gathering Friday night was equipped with a Seder plate with Chinese characteristics – red jujube paste served as the sweet charoset, and a local bitter salad green as the maror, symbolizing bondage. Though there was plenty of matzo brought in from Israel by way of Beijing, Guo Yan, 35, whose Hebrew name is Esther, recalled the more meager offerings of years past.

“It used to be nearly impossible for us to get,” she said. “We only had one piece per table, to split among 10 people.” A portion of the evening’s budget went to bringing in five members of the Li clan from the neighboring village of Lankao, where most of the 100 or so people of Jewish ancestry had no previous exposure to Jewish culture.

One Lankao resident, a 75-year-old farmer named Li Faliang, stared at his Haggadah pages from behind thick, square spectacles during the three-hour Seder.

“It’s like I’m dreaming,” he said after the meal, sounding somewhat dazed to hear of his connection to this history. He ferreted away a copy of the booklet to share with relatives who could not attend, as well as his new skullcap, which he declared “very beautiful.”

While the Chinese government enforces strict controls on religious affairs, the Seder came with the blessing of local officials, who see a variety of financial and cultural benefits in the city’s Jewish revival.

“Because Jews are only in Kaifeng, it’s a very special case,” said Wang Xiangxuan, a finance official who attended the Seder. “The government understands this, and is very supportive. The Jewish issue here is a matter of history rather than religion.”

Mr. Wang said the city government had begun discussions on preserving and rebuilding the city’s Jewish sites, including its lost synagogue.

“We can turn Kaifeng into a little Israel, which will help us develop our economy,” he said, adding that officials were also considering rebuilding a Jewish community center and museum complex that would house a synagogue, a library, a kindergarten and a Jewish snack bar, though the menu items are still a mystery. “We don’t know what Jews eat,” he said. Who will pay for the construction is a more complicated question. Kaifeng Jews involved in planning negotiations said they hoped the local government would foot the bill, to encourage Israeli investment. Last year, Israel and China signed a raft of agreements aimed at bolstering economic ties, including a $300 million partnership between Tel Aviv University and Tsinghua University in Beijing to establish an environmental technology research center in China. Israel has also awarded a high-speed rail project to a Chinese company, and another Chinese firm recently won the right to operate a port in the Israeli city of Haifa.

Jin Guangzhong, 40, whose daughter lives in Israel, said he believed Israeli investment in Kaifeng would inspire the local government to build the Jewish center “because they’ll think that Israel is a very good country, full of good will, not a country that’s fighting wars all the time.”

Many of the participants in the Passover gatherings saw no contradiction between marking the Jewish ceremony one day and Qingming the next. At a second, more intimate Seder at a private home Saturday night, Ge Huijuan, 46, said that even though she is not Jewish and is divorced from her Jewish husband, she still found it important that her daughter explore all sides of her heritage.

“We simply didn’t know until a few years ago about my daughter’s Jewish side,” she said, tucking a gold Buddha pendant under her shirt when she noticed it drawing attention. “Now, we of course ought to celebrate holidays of both cultures.”

Mr. Li looked on approvingly as a Hebrew-speaking American from Jerusalem read a prayer of remembrance for the dead originating from the old Kaifeng manuscripts. On either side of a large, golden Star of David, the black-and-white images of his grandparents stared back.

“There’s no conflict between Passover and Qingming,” he said. “They’re both about remembrance of ancestors – very similar, just with different methods.”

https://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/04/06/kaifeng-china-jewish-roots-passover/