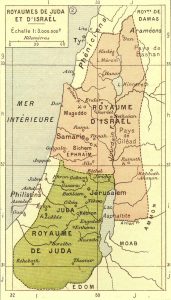

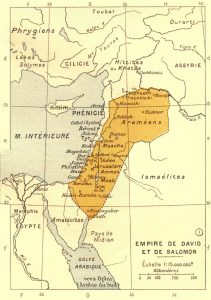

Exiled in Assyria in the 8th century BC AD, ten of the twelve tribes of ancient Israel never returned to their land and disappeared from history. According to the most common interpretations, they assimilated to the populations of the new lands where they had to settle. However, biblical texts made brief allusions to a possible survival of these tribes, and their destiny was evoked more extensively in extrabiblical texts. The possibility of an ultimate reunion between the Jewish descendants of the Kingdom of Judah and the ten tribes was quickly associated with messianic perspectives; at the moment of redemption, or when it comes near, the “lost” tribes would resume their place. This messianic dimension must not be neglected, especially if one wants to understand some of the motivations of Jewish groups who have taken to heart the question of the lost tribes in recent decades.

Exiled in Assyria in the 8th century BC AD, ten of the twelve tribes of ancient Israel never returned to their land and disappeared from history. According to the most common interpretations, they assimilated to the populations of the new lands where they had to settle. However, biblical texts made brief allusions to a possible survival of these tribes, and their destiny was evoked more extensively in extrabiblical texts. The possibility of an ultimate reunion between the Jewish descendants of the Kingdom of Judah and the ten tribes was quickly associated with messianic perspectives; at the moment of redemption, or when it comes near, the “lost” tribes would resume their place. This messianic dimension must not be neglected, especially if one wants to understand some of the motivations of Jewish groups who have taken to heart the question of the lost tribes in recent decades.

But where are these tribes? The most varied theses have emerged over the centuries, and there is hardly a continent where we have thought to find their footsteps – and where groups have believed to be the descendants: recently again, we heard in an Australian university an ethnologist’s report on a tribal group she studies in New Guinea, who discovered a Jewish ancestry and incorporates it into her mythology. From Latin America to Japan, from Kashmir to Britain, the legacy of these lost and ubiquitous tribes has resurfaced over the centuries. The British example is interesting here, since it shows the strength of the myth in environments that are not only those of colonized societies: the theories of British Israelism had a real success in certain circles of the English elite in the nineteenth century ( and harmonized well with the feeling of being a chosen people to rule the world: “the Empire on which the sun never sets”); the susbsistant groups, such as the British Israel World Federation, are now only a pale reflection.

It is therefore not surprising that the thesis of a presence of descendants of the ten tribes in Africa was also mentioned, not only by African authors. Especially since Ethiopia and the links evoked by the Bible between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba could incite speculation on the lost tribes to point in this direction.

Today there are Jewish groups active in the search for the ten tribes, who sometimes actively support the efforts of groups – in all latitudes – declaring themselves Jewish or finding the path of Judaism: we can mention the Kulanu association. These approaches are often linked to a religious Zionism, which marks the return of the “lost tribes” in a Messianism linked to the creation of the State of Israel.

However, to understand the phenomenon of black Jews, it is necessary to broaden the perspective beyond the specific question of the lost tribes and to explore the mythography of Africa as well as the representations of Africans among other peoples (especially Western). Not without underlining the links between the two in the Western subconscious: after all, were both Jews and Black embodied by otherness, associated in surplus with the negative connotation of darkness? Until the nineteenth century, there were more than one traveler to emphasize the “black” complexion of the Jews they met, or even to draw comparisons between the physiognomy of Jews and Africans.

The other historical angle of approach to the question of Jewish or Judaizing blacks is that of the integration of the Jewish heritage by the African diaspora in the 19th and 20th centuries. At first, it is a reversal of history, in which Africa becomes the source of civilizations (building on the image of ancient Egypt), and these great original civilizations were – affirm these interpretations – the fact of Blacks: a series of authors continue to develop these theses. Some have gone one step further, claiming that these blacks were the descendants of Hebrews: this other reversal takes place in a context that attempts to overcome the inferiority in which the black people are placed while finding a new way of life. history and a myth of origins; this is the context in which groups of black Jews and black Muslims are born in North America. This is the promise of a glorious future for the black race, after the passage through oppression – like the Hebrews in Egypt, redemption will follow the exile: at that time are forging plans for return to Africa, while the reference to Ethiopia will see joining myth and history, from the coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie, in the beliefs of the Rastafarian movement.

The first organized community of black American Jews was born in 1896, but is very far from orthodox Judaism, mixing Christian elements with references and practices drawn from the Old Testament. This model continues to be the one followed by many other American Judeo-Black communities, showing in passing the profound impact of Christian and Biblical themes in the imagination of these populations.

The first organized community of black American Jews was born in 1896, but is very far from orthodox Judaism, mixing Christian elements with references and practices drawn from the Old Testament. This model continues to be the one followed by many other American Judeo-Black communities, showing in passing the profound impact of Christian and Biblical themes in the imagination of these populations.

The second part of the book begins by focusing on historical accounts of a Jewish presence in sub-Saharan Africa. Various accounts of the period after the arrival of Islam evoke Jewish presences in areas bordering the Sahara, and tribes of Mali said they had Jewish origins. As for East Africa, expulsions of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula have led some to this area, and subsequent mixed marriages have resulted in a Judeo-African presence, with remains of Jewish identity under a Catholic appearance here and there .

We remain there in a historical context which, in spite of inevitable vague zones, presents explanable or at least plausible genealogies. More enigmatic are the claims of Jewish identity in the southern part of Africa, with the well-known case of the Lemba, a population belonging to the Bantu language group and having 50,000 to 70,000 members, split between Zimbabwe and South Africa . If we do not accept the hypothesis that the Lemba descend – at least partially – from perhaps Jewish immigrants from the Arabian Peninsula, it is possible that certain features that seem to bring the Lemba closer to Judaic characteristics are in fact linked to remnants of Islamic influences by the eastern coast of Africa. But the case of Lemba fascinates because of the genetic studies that have been conducted on this population and show that the structure of their DNA suggests an extra-African origin (of male ancestry) and has similarities with those of “Semitic” populations, surplus with a high frequency of presence of a chromosome characteristic of a Hebrew priestly line. Contemporary scientific research and DNA will help change the consciousness of themselves that such groups cultivate.

The different populations claiming a Jewish origin across Africa do not all intend to derive from it a conversion or a “return” to Judaism. Created in 1993 in Timbuktu, the Zakhor Association has 1,000 members, who claim to be the descendants of Saharan Jews. They see themselves as “dejected” Jews, who want to reconnect with their cultural heritage, but do not want to renounce their Muslim religion. Links are forged with groups abroad interested in the fate of dispersed populations of Jewish origin or so-called, and the Internet contributes significantly today, notes Edith Bruder, not only in the case of Mali.

The claim to a Jewish identity is developing easily in groups that have suffered persecution and repression: for example, among the Ibo of Nigeria, an ethnic group responsible for the abortive independence of Biafra in 1967, and the dramatic humanitarian situation. following this secession attempt. There are groups among them who intend to practice Judaism and aspire to recognition, others who mix Judaism and Christianity. In Nigeria, as elsewhere, visitors from the United States or Israel have emerged in recent years, ready to support these aspirations and help these groups to appropriate the Jewish tradition.

Similarly, the Havila Institute is an organization founded by Tutsi emigrants in Belgium, with its headquarters in Brussels: the genocide that struck the Tutsi in Rwanda is linked in the perception of this group to their supposed Hebrew identity – that- it also feeds on observations that emerged during the colonial period on the specificity of Tutsis in relation to their ethnic environment.

In Ghana, a group called the House of Israel is smaller in size, with some 800 members, following visions received by a Ghanian in 1976, during which it was revealed to him that he and the inhabitants of his village were descended from lost tribes. Their synagogue was built with financial help from a Jewish community in Iowa.

And we could continue, to go round the groups of black Jews on the African continent today, without forgetting of course the Ugandan Abayudaya, formally received in Judaism (or rather confirmed in their Judaism) by orthodox Jewish rabbis in 2002 as Religioscope had related.

An article in the Jerusalem Report (September 29, 2008) updates this information. Some 1,050 Abayudaya are now officially recognized as Jews, following new group receptions, the last one in July 2008. In this last series of 250 converts, not all of them came from the Abayudaya group: about 50 were Apaci, at the origin of Adventists, who began moving towards Judaism around 1995, and a few others came from other places in Uganda, and even other African countries. The black Jews of Uganda are thus no longer limited to the original group, and this development points to further cases of conversions across the continent. The month of July 2008 also marked an important development for the Abayudaya: the reception of the first rabbi of their community, trained and ordained (in May 2008) in an American rabbinical school (Ziegler Schhol of Rabbinic Studies, Los Angeles). The integration of groups of black Jews in the classical currents of Judaism is progressing.

An article in the Jerusalem Report (September 29, 2008) updates this information. Some 1,050 Abayudaya are now officially recognized as Jews, following new group receptions, the last one in July 2008. In this last series of 250 converts, not all of them came from the Abayudaya group: about 50 were Apaci, at the origin of Adventists, who began moving towards Judaism around 1995, and a few others came from other places in Uganda, and even other African countries. The black Jews of Uganda are thus no longer limited to the original group, and this development points to further cases of conversions across the continent. The month of July 2008 also marked an important development for the Abayudaya: the reception of the first rabbi of their community, trained and ordained (in May 2008) in an American rabbinical school (Ziegler Schhol of Rabbinic Studies, Los Angeles). The integration of groups of black Jews in the classical currents of Judaism is progressing.